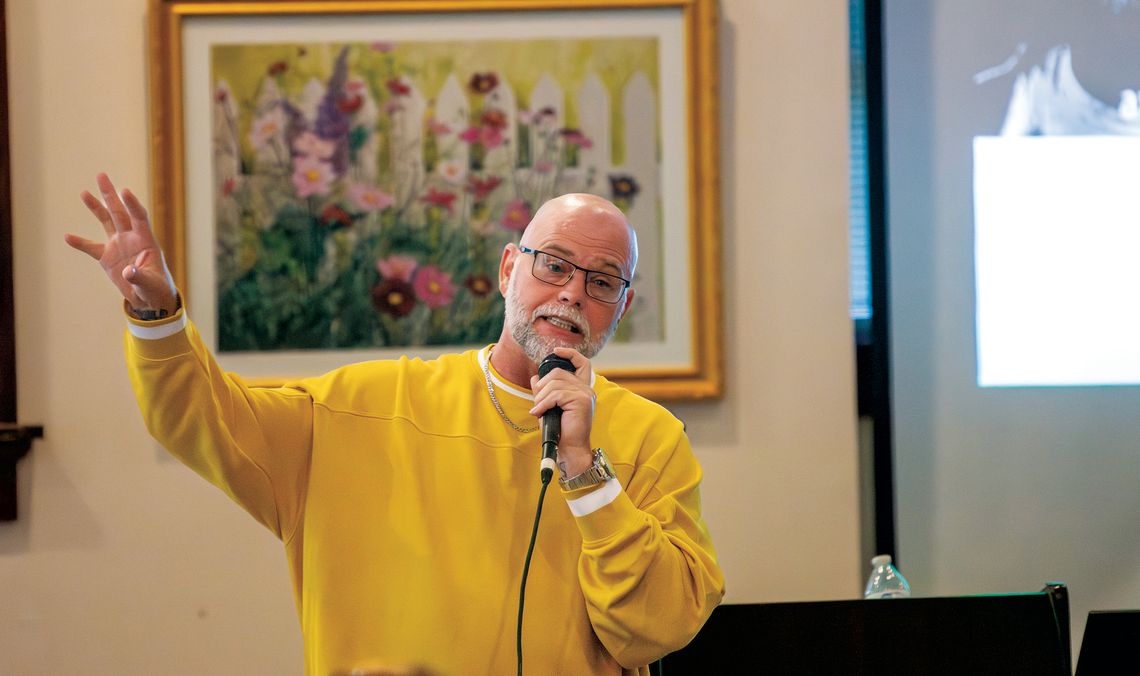

Noted recovery advocate Jimmy McGill shared his personal journey toward sobriety on Tuesday during the Celebrate Recovery Month event in Parsons.

Labette Center for Mental Health Services in Parsons sponsored the event at the Carnegie Arts Center. McGill was the main speaker, but three people involved in LCMHS recovery programs as well as three peer support leaders had testimony presented.

The main message on Tuesday was hope, hope for recovery, hope for a restored life.

In 2017, McGill became the first person on parole to be appointed to a state position under then-Gov. Asa Hutchinson. He later founded a nonprofit called Next Step Recovery Housing. In May 2022, Hutchinson granted McGill a full pardon.

McGill is the executive director at the National Peer Recovery Alliance. Formerly the director of Peer and Recovery Services for the state of Arkansas (2018-2023), McGill’s personal journey fuels his commitment to advancing recovery services nationally. A founding member of the SAMHSA Region 6 Peer Support Advisory Committee and inaugural chairman of the National Association of Reentry Professionals, McGill leads efforts in peer support and reentry advocacy, LCMHS said in announcing Mc-Gill’s appearance.

McGill, 48, shared details of his early life, when he was neglected by his drug addicted father, suffered other abuse and spent time with an alcoholic grandfather. He also discussed his years of addiction and his sobriety journey, which started more than 10 years ago with an assist from his God. Before sobriety, McGill collected 19 felony convictions and served six prison terms.

“The only reason I’m clean today is because I have a God that can turn broken pieces into master pieces,” McGill said.

His addiction lasted 23 years. He used a variety of drugs, and his drug of choice depended on availability.

Even today, he said he is learning about his childhood trauma and exploring the reasons he did what he did and what he still does. For example, he still takes long baths or showers. In his childhood, at the age 11 or 12, he would visit his grandfather’s home and lock himself in the bathroom, get in the tub and stay there for hours. The house itself smelled like liquor, poop and pee, he said. But the bathtub, “That was the first place I felt safe. So here I am, three decades later, taking a two-hour shower like a teenager,” McGill said.

His dad was in and out of prison in his formative years, McGill said. He remembers seeing pictures from his youth and learned that he visited his dad in prison. His uncle used him as a mule to pass drugs to his father in prison during family visits. Children weren’t searched before visiting family in prison, he said.

He joined a gang while growing up in a household where he represented the third generation in addiction and dysfunction. The family had a cycle of poverty and brokenness that was passed down to the next generation.

He said he needed his father, but his father needed the drug. When his dad had the drug, he could be present. But his memories include doing abnormal things, like holding his father’s arm so he could find a good vein. His father also introduced him to scales (used to weigh drug quantities) and showed him how to bag up chemicals.

“So that should paint a picture of the atmosphere of neglect that I grew up in, and in that atmosphere, a thug was born, because my father was the second generation of chaos in this cycle, and his substance of choice made him negligent. My dad loved me the best he could, but he died from an untreated disease. That’s it in a nutshell,” McGill said.

His father didn’t know about available treatments, about recovery. He didn’t know he didn’t have to shoot heroin or Dilaudid. He didn’t know that he didn’t have to go in and out of prison, he said.

See SOBER, Page 3.

The life of crime started early for McGill. He remembers seeing other kids at school, who appeared to have functioning families, riding bicycles, go-karts, Big Wheels. He didn’t have that stuff, so he stole it.

His first time in long-term lockup was a sentence served in a juvenile facility.

“I’m here to tell you this, we need better juvenile services all across the country, because they locked me in a cage, and I ended up going to prison six different times.” He said you could take all six of his prison terms and boil them in a pot and the result wouldn’t be 10% as hard as that juvenile term, he said. Kids were mean and abusive. Staff was abusive.

“It was literally hell on earth, and it set the tone for the rest of my life.”

His gang affiliation led to other prison terms as drug addiction fueled his life of crime. Throughout most of his criminal career, a neighborhood cop, Kirk Lane, arrested McGill many times, as well as his family and friends. McGill said he watched Lane’s career blossom, from patrolman to detective to captain of the narcotics division.

“I just did it from the back seat of the cop car, like I was instrumental in him advancing his career.”

Lane is the Arkansas drug czar, a position he’s held since 2017.

McGill also shared some of his misfortunes in his career. To feed his addiction, he stole things. He once traveled 30 miles away from home to burglarize a house. He said an area Hastings store would buy used books or DVDs. He took the stolen loot in pillowcases to Hastings. He expected to get $2 or $3 per item. He learned his ill-gotten booty included rare volumes. The DVDs featured anime and the clerk told McGill the items were valued at over $1,000. There was not that much cash in the register so the clerk called the manager.

The manager looked over the DVDs and remarked at how rare the items were, which Mc-Gill said he received as a gift. One was especially valuable, and the manager told McGill someone wouldn’t just give that item away. The manager also realized that he had many of the same items in his own collection.

“So don’t tell me that God doesn’t have a sense of humor, OK. Because that man went to the next DVD and he said, ‘I’ve got this one, too.’ Out of all the houses I could have robbed and all the stores I could have went to I tried to sell that man his own stuff,” McGill said.

McGill received a seven-year sentence and was released after 14 months, still in the throes of addiction. As an addict, he fell back on old habits. He and some friends planned to steal a safe, but McGill was the lookout, giving him options if caught. McGill was smoking while the burglary took place. He tossed his cigarette in the garage after his friends removed the safe from the structure.

Police were able to link Mc-Gill to the crime from DNA he left on the cigarette, he said.

He received another prison term. The next time he got out, he decided he was done with theft. He moved on to drug dealing. McGill said his dad’s house was in a predominantly Black neighborhood in North Little Rock, Arkansas. He was the only white person in a large area. He said he was arrested by Lane after selling drugs to a confidential informant.

He walked out of prison for the sixth time and wound up in a recovery group with people who were fighting addictions. They told McGill he was in the right place, asked him to keep coming back and told him that he could recover.

He got clean and has stayed clean since Feb. 27, 2015. He wrote a book, “From Prison to Purpose.” He’s working on a second book now.

Since then, he started a non-profit, traveled the world, shared he stage with Jelly Roll and a president.

“I have done it all through recovery. There is nothing special about me. Any one of us can recover, and we do recover. I found my room, I found my tribe. And, all of a sudden, recovery had become cool. All of a sudden, I didn’t need to stay stuck on stupid trying to pilfer through a box full of phone chargers for 10 hours. I didn’t need to be pilfering through dirty clothes. I had found hope, and I had found help,” McGill said.

He also helped others through addiction and wanted to share his experiences with others still.

With state financial help, and the help of Lane, who was state drug czar, a peer support program was created for inmates leaving custody. The program started with 16 inmates in a jail. After a year, 12 of the 16 had not reoffended. Normally, a person released from jail would reoffend within three days to six weeks of release. Six years later, those 12 are still productive members of the community.

From the data collected in that program, he created 54 others and still had other work to do.

He’s also created programs to help women and families. He created the housing program to help those transitioning into society from lockup, Next Step Recovery Housing, which started with eight beds and now has 53.

He is now married and is raising a teenage son. He is the founding executive director of the National Peer Recovery Alliance. He also signed a $5 million contract with the Arkansas courts to add a peer support group in all of the specialty courts in the state, all the mental health courts and all of the veterans courts.

“Do not write your lived experience off. We all have a place at the table,” he said.

“So not only did I learn to become a husband and a father, but now I’m able to transmit that to other men to help them become a husband, a father, a son, and none of that would have been possible had I not spent 23 years in addiction, had I not gone to prison and had I not went through all those trials and fires of growing up in child neglect.”

And his recovery continues with the help of clinical staff and therapists.

He told those attending Tuesday about how their addiction can serve a purpose for the greater good.

“All these things became onthe- job training to reach a population of people that society says is unreachable and unteachable. You are uniquely qualified to go back into the fire that once consumed you with a bucket of water for those still burning. That is recovery,” McGill said.

“So no matter how dark your story looks right now, if you continue your journey of recovery, there is no ceiling when it comes to what God does in recovery.” Recovery happens one day at a time. Keep doing what you did yesterday.

“And every time we think we hit an all time high, God takes us a level up, and that has been my story.”

Monica Simpson, public relations specialist for LCMHS, showed video interviews of three peer support leaders at the center. She also read testimony from two persons with mental health conditions involved in the center’s Individual Placement Supports group, which helps participants find and maintain jobs.

A third discussed her addiction to methamphetamine in a video interview. The woman, identified as Tammy, was abandoned by her family at a young age. Her life was a struggle and included a heavy meth addiction. She said she would spend $1,500 in four days on meth. She served time in prison and in rehab and decided to change her life.

She has been sober 210 days as of Tuesday. She encouraged others to find help to get sober and work through the recovery process.

Good things have happened in her life since she became sober, Tammy said in the interview.

“Make the right choice. And before you can do that, you gotta be honest. And honesty starts within yourself first, and then you can be honest with everybody else,” Tammy said. “I want people that’s high to see what a great life it is to be sober. I want to try to help anybody I can.”