OSWEGO — The Oswego Historical Museum and Genealogy Center on Saturday honored the memory of Staff Sgt. Joe Schreppel. Schreppel, a tail gunner on the Jolly Roger, a B-17, was killed during a bombing run during World War II. His body has never been recovered.

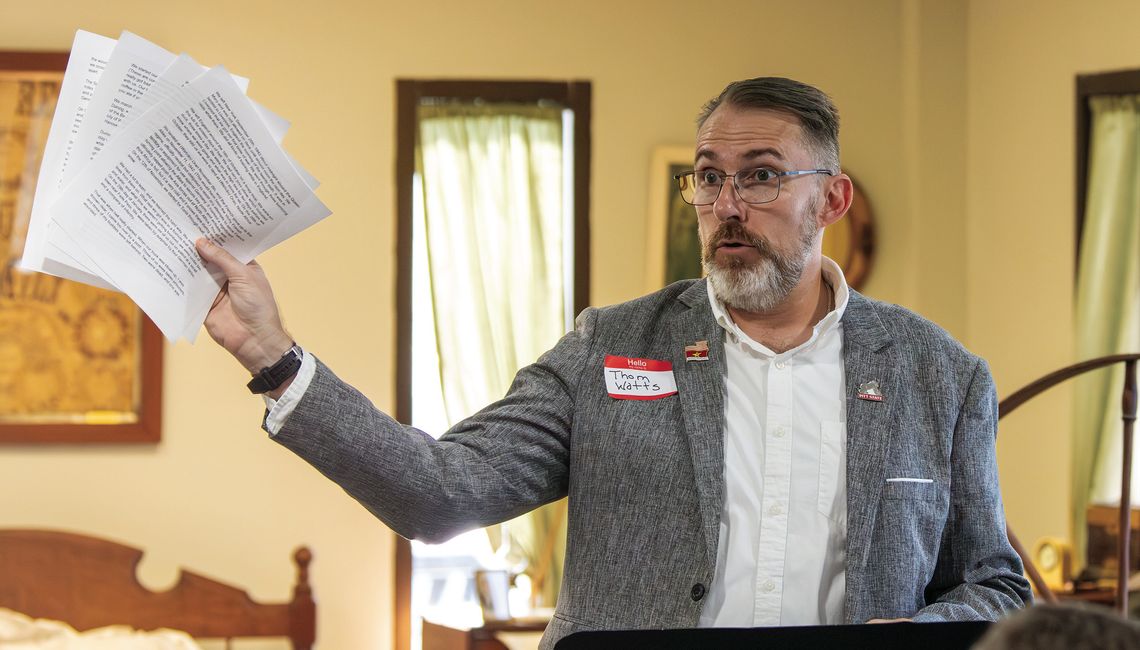

Schreppel’s story was one of several recounted on Saturday, as Janie Allison shared a story from her parents’ marriage shortly after WWII, Thom Watts read from Gene Newbanks’ POW journal. Newbanks is Watts’ grandfather. Max Bringle shared memories of Mitchell Bringle, his father, who served aboard the USS Yorktown in the same war.

Military histories and other online sites have information on Sgt. Schreppel.

Thom Watts shared the history. Schreppel was on the B-17 Flying Fortress that carried 10 crew members. The plane left the United Kingdom on a bombing mission to damage military factories in Germany. The mission was critical to impact Germany’s ability to develop its weapons.

The Jolly Roger was attacked by enemy fighters and crashed on Aug. 17, 1943. Five crew members parachuted from the plane. Crew members helped Schreppel, who was wounded by flack, with his chute. Of the five, one died in his landing. Schreppel was not able to control his chute and hit a tree. Though mortally wounded, he started a fire to attract help, and two young boys responded. Before he died, he whispered his name to the youth, who wrote it as Joe Sharpel of Pittsburgh, instead of Schreppel of Pittsburg.

The Germans took possession of Schreppel’s body after it had been taken to a mortuary in Zoersel, Belgium. His body has not been seen since and is thought to have been buried in the Ardennes American Cemetery along with 5,162 other Americans. Family has given DNA samples in the hope of someday identifying his remains.

The day Schreppel died was dubbed Black Tuesday because during that Allied bombing mission, 376 B-17s left England for the two-pronged attack on war equipment factories. The U.S. lost 60 B-17s to enemy fire and 650 airmen died, or were wounded or captured, according to Dr. William Pace Head, chief historian at the 78th Air Base Wing, Robbins Air Force Base, Georgia.

A family in Belgium worked over the decades to find and communicate with Schreppel’s family. Their search was hampered by the misspelling and the fact that he was from Pittsburg and not Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The townspeople kept Schreppel’s parachute and a leather glove. They gave the Germans his dog tags, which were lost. Eventually, the Schreppel family linked up with the Belgium family of Gustave Cryns in 1999. The Cryns family spent weekends searching for the airman’s family; these weekends were eventually called “Schreppeling.”

Members of the Schreppel family have either lived in Belgium because of work or have traveled there. The search for his remains continues, and the Belgium townspeople where the Americans are buried take care of the Americans’ graves and honor their sacrifice each Memorial Day.

After Allison, Bringle and Watts spoke, Jeff Schreppel made a special presentation, and the museum presented an Honor and Remember flag to Sgt. Schreppel’s last living sibling, Barbara Shelton, who attended Saturday’s event.

Schreppel said his brother served in the airborne and visited Bastogne, Belgium, and learned about a beer brewed there called Airborne beer. He shared a cup from which those in Bastogne drink the beer, as well as a bottle of the beer.

Bringle shared the Honor and Remember flag’s symbolism. Red stands for sacrifice and bloodshed. White stands for purity of sacrifice. The blue star overlaid by a gold star reminds those families impacted by the sacrifice of those serving.

Kris Redburn of the museum handed the flag to Shelton, who cried as she accepted it.

“This flag … is presented unfurled and it’s supposed to never be folded back up,” Redburn said, and it’s to remember Schreppel’s life and not his death.